Phenomenology is Sinful

St Thomas says curiosity is a sin and a species of pride. It seeks knowledge that either distracts us from pursuing, or is cut off from, our final end.

intellectus… natus est omnia quae sunt in rerum naturae intelligere. (Contra Gentiles 3.59)

bonum non solum habet rationem perfecti, sed perfectivi (Quaestiones disp. de veritate 21, 3 ad 2)

Philosophy is, I think properly, translated as the love of wisdom, and wisdom obtains the knowledge of things as regards their proper end. A foolish man, for instance, tries to avoid failure, thinking that avoiding failure leads to success. A wise man knows the contrary, that failing well or a willingness to fail is material to success. And life is full of like instances, where the pursuit of a false means produces the exact opposite of the intended result. It turns out there is likely no more brutal subjugation of and denigration of women than in a society where they have learned to will a strict equality with men by aping, often the most base, masculine traits and activities. Modern feminism is foolish, it seeks means that are not ordered towards the intended goal: the flourishing of women. The wise man knows the means ordered to the end he intends.

In the argument that follows, I demonstrate that phenomenology, as a stand-alone philosophical method or approach to doing philosophy, as one finds in thinkers like Husserl, Heidegger, and Levinas, is not merely foolish but vicious. It’s error can be simply stated and resembles the previous two examples: it intends knowledge of reality through the false means of the making sense of the first-person human experiencing of reality.1 Unfortunately, the study or interrogation of the first-person human experiencing of reality does not lead to the knowledge of reality itself or even a practical enrichment of one's experience itself. I argue conversely, that, as regards our practical life, this focus distracts from the proper objects of desire and action and thereby leads to a desiccation of human experience.

Of course, phenomenology does produce a sort of knowledge. It produces a vocabulary and (unfortunately!) also a syntax for making sense of human experiencing, and it does produce a sort of knowledge thereof. This I cannot deny. I only deny that this knowledge can be good for anything outside of this scope: a theoretical appraisal of human experience or consciousness, and things as they appear to human experience. This has its place in philosophy2 but it needs be circumscribed and/or extended by other philosophical disciplines like logic, ethics, aesthetics and metaphysics in reference to semiotic, empirical and intersubjective realities beyond the first-person experiential.3 Due to this limitation of both method and scope, I argue that phenomenology alone cannot by itself lead to an adequate understanding of causes, and particularly final causes of things and actions. As a result, the method of phenomenology by itself does not tend to perfect practical knowledge or wisdom. Hereby stands the claim that it produces a vicious knowledge. Curiosity, a species of pride, is what seeks the knowledge of things which cannot be ordered to the Good, it seeks the knowledge of things that distract from or obscure our true end as humans.

There are other devastating critiques of phenomenology, Wittgenstein's private language argument is one for instance, but due to the apparent glossolalia of its most prized practicants, phenomenology has proved a difficult target to hit. Phenomenology is a way of describing experiencing, and tends to respond to objections with more of its magic bullet, with more describing of experiencing. In any case, this argument, I think, is novel because it is a critique of phenomenology from the point of view of moral philosophy, and the critiques I have seen come from philosophy of mind, language, metaphysics and epistemology. So here is the argument roughly sketched:

Ancient philosophy sought to know reality by arriving at knowledge of the form of things. These could be material things like rocks or immaterial things like justice. The form is that through which something is intelligible or known as itself.

The lynchpin of the ancient philosophical enterprise was the form of the Good, it was that which should sought to be both known and desired above all.4

The Good established a harmony between theoretical and practical knowledge and reason, contemplation and desire, between thought and action. Yet this depended on a common object that could be both contemplated and desired. 5

And philosophy could conceivably, in this universe, itself be good, it could help you live better, if only you better comprehend the form of the Good, and thereby better desire it and live it.

Modern philosophy introduced a skepticism concerning if we can know reality, if we can get at the real objective form of things. Cartesian skepticism interrogates the difference between appearance and real. Kantian skepticism interrogates the conditions of the possibility of knowing at all.6

Phenomenology is a method for resolving the problems introduced by the Kantian form of skepticism, the—how is knowledge possible at all?—sort of question. Phenomenology claims to secure knowledge of the form of things through uncovering the structures of our first-person experiencing of the things. E.g. so you will know the form of justice by your experiencing of justice as it presents itself to human consciousness. Like most sects, it takes a good idea and over-extends it. Our knowledge of reality is mediated by first-person experience, a good reason to get clear about what experience or consciousness is. But getting the structure of first person experiencing right doesn’t inversely lead to a proper knowledge of reality.

From the point of view of practical or moral philosophy, it's a good example of the fallacy Whitehead describes as of misplaced concreteness.7 Basically the human mind has to use the power of abstractions to try to generalize and make sense of reality with words and concepts. Whitehead uses the example of an earthquake. The earthquake can be scientifically experienced by observing a seismograph, or by enduring the physical event itself. Both the geographer and earthquake survivor are going to abstract from the reality of the earthquake to make sense of it. But in very different ways. The scientist will be able to give an exact measurement and quantification, the survivor a narrative. One observes only with the eyes the movement of a needle, the other is shaken and battered by the quake itself. One might say the survivor´s experience is more concrete, and in a sense it is, but if we think about preparing for future earthquakes, the more abstract and precise knowledge of the geologist may be more helpful in predicting future action. Whitehead invented this fallacy to express his concern about the progress of science, about practices of abstraction that limited the reach of what science could make sense of. He notes, for instance, notes that Newtonian physics reduces the universe to Matter in Motion through Space and Time. This is an instance of misplaced concreteness because this picture of the universe excludes chance, cognition and other constitutive factors of the universe which it cannot factor into these basic abstractions. It thereby unduly limits the scope of science. But moral science is not about discovery but good action. Trial and error is too risky here, as one abortive trial could take a life or do serious harm. In moral philosophy, the desired level of abstraction is one that helps us desire the proper end and decide the proper means to this end. Basically in the case with phenomenology, as it applies to desire and deliberation, the perfect object of action isn't going to be an abstraction of the experiencing of the thing or action but often the possession of the thing, completion of the action, and the attainment its objective result or end. Aristotelian moral science is more about measuring the mean to find virtue—like the geologist— than trying to intuit norms from the immediate abstraction or narration of lived experience. As Edith Stein points out8, if phenomenology is good at describing how things appear, it struggles to make clear why things are there. It struggles to comprehend the objective nature of things and acts tending towards specific ends. This blind spot concerning final causality is a clear problem for the ethical life, as good action requires having insight into things and acts, not merely as they appear or how they are experienced, but also as they tend by nature towards their objective ends.

This misplaced concreteness thus opens up an indissoluble gap between theory and practice, between speculative and practical reason. What we desire is derivative of what we know, and here we know the first-person experiencing of a thing, action, or end and not the thing, action, or end itself. Many ends of action do not present themselves immediately to human first-person experience at all. Thus, the common object between speculative and practical reason disappears, and with it the possible fruits of philosophical inquiry. Desiring the thing, action, or end itself and desiring the experience of the thing, action, or end are two different things, with the former being far more excellent and effective in the practical life. Experience is slippery, and fickle, and varies more from person to person, and thus is liable to widely varying descriptions. Thus it's important to desire something that transcends experience to grow as a human, its also important for social cohesion as well—the more objective things, acts, and ends are, the more easily shared between people. Thus, this first-person experiential grounding of concepts and ideas works to undermine the common good.

Furthermore, desiring the experience of the thing is never going to produce the same experience as desiring the thing. To desire justice isn't the same as to desire the experiencing of justice. To desire mystical experience, for instance, is a guarantee that one will not be given a mystical experience. If one quite simply desires God or seeks to penetrate a particular divine mystery in prayer, then it is possible one will be given a mystical experience. Thus the sort of knowledge produced by phenomenology is always going to be retrograde in terms of practice as it can´t adequately clarify what we are supposed to desire, and in fact it will tempt us with desiring the givenness of the thing to consciousness rather than the thing itself.

This presents a catch-22. If the objects of practical reason are desired simply, they cannot be perfected or perfectly known through the phenomenological method, which seeks to know the objects of practical reason, so the ends of things or acts, but only as the end is experienced at the first-person level. If one desires instead the first-person experience of a certain action, rather than the action itself, then the experience itself, which is contingent upon desiring the action, not the experiencing of the action, itself disappears.

A thoroughgoing phenomenological philosophy is sinful. It produces a sort of first person experiential knowledge that falls into what St Thomas would define as the sin of curiosity, a species of pride.9 Curiosity seeks knowledge of what cannot be ordered toward the good. This first-person experiential knowledge cannot be ordered towards the good because it cannot be desired as the proper object of the most crucial acts of human life, nor can it approach the status of our highest end or transcendent good, capable of properly ordering our actions and the social order.

The Tennis Parable

In order to further elucidate the problem, I came up with a parable about tennis instruction. So let's start with the ancient study of tennis. In the olden times, in order to learn how to play tennis, a teacher would show you an ideal form. You might look at various pictures of the ideal serve, forehand, and backhand. And then you would desire the form, you would try to reproduce this form in action. And learning the game was in part a negotiation, often with the aid of a teacher, between contemplating the proper form, desiring it, and putting it into action. Of course this isn't ancient, this is how we basically learn any skill even today. We are shown the form, we practice reproducing it. Without seeing the form, we cannot desire it or practice it well.

Now consider a new type of tennis coach that begins to doubt whether there is such a thing as an ideal form for a serve or for a forehand or backhand. He views the previous method of helping students approximate an ideal form as harming his students: that they weren't enjoying the game because of the terrorizing presence of the ideal forms and suspected that fear of not approximating the proper form caused them to hesitate and crippled their ability to play. The presence of an immediate, ideal, unchanging, external form stunted their ability to develop their own authentic form of playing tennis from within the game itself. Furthermore, upon further study of the all time greats, he finds a surprising variance in how the greatest players did in fact execute their serve, adding to his skepticism that there is such a thing as a proper form. This coach comes to believe that the presence of a universal ideal form was limiting their ability to access the proper form through the playing of the game itself. He thinks that through the playing of the game itself each student will arrive at his own proper form, should they have the right disposition toward experiencing the game, and learning from their experience playing the game. And this becomes the task of the new coach, to unveil the proper manner of experiencing tennis. Thus, though he already learned tennis the old way, he desires to teach students a new way: that they will learn to play tennis both by playing freely with no instruction or correction and also through learning to identify the structures of experiencing playing tennis.

This coach believes the proper form for playing the game will reveal itself to them through their experiencing of the game itself, as well as the mystery of the meaning of the game itself.10 This new teacher claims that the original meaning of tennis was often superficially reduced in the past to being about winning points and matches. He claims his method will disclose the deeper meaning and mystery of the game. Seems intuitive enough. So the teacher gives them no instruction or correction as to the proper physical form of the game, stance, balance, arm movement, etc. Instead, he lets his students play the game without his intervening. He does allow them to pause the game and troubleshoot on matters of form that they are dissatisfied with from time to time. If asked for advice on form, he can and does give it with some hesitancy, while emphasizing they should develop their own individual style of play in the context of playing the game. Yet, when the coach observes poor play he is more likely going to attribute it to a deficit in authentic play, in an experiential failure to participate appropriately in the game—e.g. a lack of intensity or care or determination—rather that a problem of inadequate strategy or physical form.

Yet the teacher does think he can, through his efforts, allow the experience of the game to be more effective in transmitting its own proper form to each student. He insists that all the students come to a class for 3 hours twice a week, where he elucidates the primordial structures of experiencing tennis to the students. If we take Heidegger´s Sein und Zeit as a template, each 3 hour sitting of the class covers one of the following topics.

(In-der-Welt-sein= Being-on-the-Court) So this refers to the player's fundamental existence within the court, considered not just as a physical location but as an environment where the player's identity as a tennis player is disclosed. The court is the "world" of tennis and the player is situated within it, interacting with its conditions.

(Mitsein= Being-with-Opponent) This refers to the player’s existence as always in relation to the opponent on the court. Tennis is never played in isolation—it is always an interaction with an other player.

(Zuhandenheit= readiness-to-hand-of-Racquet) For the tennis player, the racquet is encountered not as an object for detached observation, not as present-at-hand, but as something ready for use, something the player uses skillfully without reflecting on it as a separate entity. The racquet’s readiness-to-hand becomes manifest through skilled play, where it functions as an extension of his body rather than as a distinct object.

(Vorhandenheit=Being-present-as-an-Object/Tennis-Ball/Racquet/Court/Net) The objects of the game, when considered from outside the playing of the game itself, can be understood as present-at-hand. These things become objects of speculation, something you examine or consider, such as during a pause between sets. This mode of relating to the objects of the game does allow for players to try to pause, consider, and tweak to improve their form when their play displeases them.

(Geworfenheit=Thrown-Serve) Athletes find themselves thrown into the game, much like the existential thrownness of life, where we find ourselves in a context and drama we did not choose. In tennis, thrownness is primarily felt as the player is thrust into action (as with a serve)—not by choice, but by necessity. A tennis player has to respond and consent to the circumstances of the match which he did not choose or will. He must embrace the exigencies and contingencies of each individual game that he finds himself in.

(Sein-zum-Tode=Being-toward-Match-Point) Match point is the equivalent to the moment of death of a game. It is a finalizing moment that confronts each player. In his awareness that the game could end, that he could win or lose, each player is forced to embrace their own limitations and potential defeat, forcing authenticity in how they play and practice. Players may experience anxiety as match point approaches or even as they reflect on the finality of the game itself. Making use of this anxiety before match point and turning it into intensity in the game and intensity in training is paramount to authentic tennis play.

(Sorge=Care-for-the-Match) Care is the fundamental level of commitment to and investment in the game, in the outcome and progress of the match. Players show care for how each point is played, how strategies unfold, and how they navigate the match. Care propells the player’s attention and effort.

Ok, so list continues down below for those with time to lose11 , but you get the point. Rather than study proper foot placement for a serve, the student of this new school of tennis will hear a three hour long lecture about the existential comportment of being-toward-match-point. Basically a fundamental category of the experiencing of tennis. They will be taught this theoretical apparatus with the expectation that it would somehow aid them in playing well, or in allowing them to experience the game in such a way as to arrive at the proper form. Also poor performance will tend to be cashed out in terms of deficits in these categories of experiencing tennis—e.g. an absence of care, an anxiety about match point, etc.

So what happens? Habitual attention plus vocabulary is going to produce knowledge. So these students will be taught to hone in on their experiencing of the game and given a refined vocabulary for making sense of this experience. As a result they are going to learn a lot on this front. They will learn to speak articulately about what one experiences when one plays tennis. The students of this school can watch tennis and have fascinating conversations about various matches, what the players are going through in terms of their interior experience of the game. And it wont be strictly book knowledge, they will learn to make sense of their own experience playing the game and on this basis understand what others are experiencing. Their body of knowledge gives them an unusual level of erudition and insight into the lived experience of the game as commentators.

They could even become gurus themselves of a sort. They could offer advice about how to approach experiencing the game. Perhaps even some professionals, when in a slump, turn to these students to cash out their problems in terms of their inauthentic experiencing of the game, or an existential wrinkle in the wrist-racquet relation. Placebo´s work and this could offer more, maybe a player really did fear match point in a way that was psychologically destructive. This sort of approach could be akin to mindset training specifically for tennis players. Thus, when circumscribed to the psychology of the game, perhaps this method generates some insights. Furthermore, if someone sought to dramatically alter essential aspects of the game, say remove boundaries, replace the racquets with cricket bats, perhaps no one would be more equipped to cash out the experiential effects of these changes at a theoretical level as one of these new students of the game.

But there is only one problem: they can't play. They will never learn to play tennis well without being taught the proper form, and without this form being drilled into them. Perhaps the game is 90% psychological, 10% physical, but proper bodily form is going to be material to an effective method of instruction in any case and its missing here. It’s a classic instance of misplaced concreteness: in this case the focus, vocabulary and concomitant knowledge serve to veil, rather than disclose, the proper form of the game, making the means inaccessible and obscuring, if not diverting them away from, the end. These students will be sub-rate players because the proper form is not accessible through the speculative knowledge of how to experience authentically or through the authentic practical experiencing of the game itself. Without instruction and coaching that helps impart an ideal physical form to conform to, these players will develop bad habits, and bad form, and they aren´t going to be able to break these without external help, without someone teaching them to recognize and approximate the proper form, which will feel increasingly uncomfortable for them the harder these bad habits are baked into their tennis game. And without being taught the proper form they will never even be able to access, at the practical level, the experiential aspects of the game for themselves, a game they learned to speak so articulately about. In fact, the more they study the more frustrated they will become. Because they will desire what they contemplate, and that is the experiencing of the game, but the true enjoyment of the game only comes through the proper form and the desiring and practicing of this form. Thus the students will gradually become frustrated and grow to hate playing the game, because they won´t be competitive, and, as a result, even the experiencing of the game will elude them at the level of practice. Readiness-to-hand-of-the-Racquet isn't the same experience when you can´t ball.

It would also be a temptation, if not a necessity, to alter the end itself: whether the students would desire to win or to desire a particular mode of the experiencing of the game where the true meaning of the game would appear.12 If they were taught to desire to win, or how to desire to win in this class, in terms of generating a mindset or subjective mood, this too would be a supreme source of frustration. As winning would only come through the knowledge of the form that had been veiled from them. But perhaps they would settle for desiring the mere experience of playing or, what is far more ambitious, to uncover the true, hidden meaning of tennis through the raw experiencing or playing of the game. Over time, they would develop passable but never excellent skills, and the temptation would be to grow content merely with desiring playing and giving up any concern about excellence or winning. This reveals again the fundamental catch-22. If being-towards-victory is a fundamental category upon which the meaning, nay the mystery of tennis, presents itself, then these guys are going to be frustrated, as they will be sub-rate players and will often lose which will threaten the persistence of the frustrated desire itself. If instead, they alter the end to conform to the object of knowledge, that is the proper experiencing of the game, then they are content to play without desiring to win, and, if enjoyable, the experience of tennis itself disappears, it will not be accessible. The best solution is to avoid the practical activity of playing altogether, and for these students of the game to focus on talking about the game, which is what they are good at.

But this parable helps clarify why I think phenomenology is sinful: it directs attention toward first-person experiencing, by means of a vocabulary for making sense of this experience, which produces both a theoretical and practical knowledge that is not and cannot be oriented towards perfection in practice. Perfection can only be learned by imitating and replicating the ideal external form. In the Summa (II-II q. 167 a. 1), St Thomas says a sinful inordinate appetite for learning, or curiosity, occurs in two instances: (1) when one learns frivolous things and neglects his duty to learn what is essential to life or to his task. The tennis example clarifies how the ideal form cannot be intuited through either the study of the structures of experiencing of the form or living within the proper authentic experiencing of things or acts. Knowledge of the form of the good is not communicated to us internal to our experiencing of life itself. And, curiosity is also present in an inordinate appetite to learn (2) when things are sought to be known are not ordered toward God as their final end. Here as well, the fundamental impulse for the new method of learning tennis was a skepticism about both the ideal forms and the traditional end of the game, winning, and a desire to let the both the authentic form and the mystery of the meaning of the game manifest itself through the playing of the game. Here attention and vocabulary are focused on generating a knowledge of experiencing which is not ordered to the proper end of playing well or winning. The parable helps us see who phenomenology generates knowledge that is theoretically interesting perhaps, but practically a distraction from more important obligations, and it is also not ordered toward perfecting us towards the highest end of human life.

This phenomenological tennis cult is also difficult to confront, because to the objection: “this stuff your learning isn't helping you play or win”, we hear from our coach and his students: “that's not the point! you philistines, brutes! we are seeking to know the meaning of tennis as revealed through the authentic experiencing of the game!” The difficulty competing seems to make it a foregone conclusion that the revelation of the hidden meaning of tennis to the disciples of this school will have little to do with points or winning matches. As a consolation, they come to possess a certain degree of unfounded arrogance almost proportionate to their lack of prowess on the court. They are members of a heideggerian13 gnostic cult of tennis, a cult that attracts the unathletic and slothful, but verbally adroit, those who either can´t or don´t want to put in the work to reach excellence.

A Second Application: Sexual Ethics

Another example: Consider a pervert who hears fornication is the most pleasurable when you truly love your partner, and then seeks to truly love his partner more for the purposes of sexual pleasure. Well, even if his thesis is true, he is never going to get there so long as his intention is for his personal pleasure, as true love wouldn't seek this. If he ever intends the act according to his plan, his own experience will not be his object. Yet, ends which cannot be mediated by an experiencing are not discoverable by the method of inquiry. So here as well the structure of the catch-22 rears its head. Yet, one could anticipate an objection: one can also imagine a more subjective end of a loving act beneath which he should subordinate his selfish desires. Perhaps he intends to experience the act one of self-giving to another person, as being understood to establish an unbreakable bond to the other person. This sort of subjective criteria would be difficult to control for or identify objectively—consent as a criteria has the same problem— as to whether he or anyone satisfied the condition, but it could entail a real shift in his mindset towards unselfishness and charity. Even still in this case, according to the natural law point of view, if he's intentionally avoiding the proper natural or objective end of the act, i.e. the creation of a child, the act cannot be properly called loving. Love wouldn't intentionally obstruct the end or perfection of the action from being fulfilled, even if the possibility of its being fulfilled is unlikely.

To make subjective criteria normative for sexuality, whether a feeling, sense of commitment, or mere consent, is an instance of misplaced concreteness. The primary and natural end of the act is thereby not captured in these abstractions and cannot be. A defect that comes with the most grave consequences. Neither can the knowledge of this end be garnered through the experiencing of the act. He might be faced with the natural end of the act a few months later, something he never intended. But he´s a pervert and doesn´t think of this and if he does he can´t see how the end provides normative criteria for the proper action itself. He's already ruined his moral conscience and ability to comprehend this through the study of nature (the relation between formality and finality). He can thus only know the proper natural end of the action, and order the action towards this end, by accepting external, likely religious, authority.

But the question is crucial: does he desire a mere “loving experience of self-giving” and/or also a child? Is his end a subjective feeling or meaning or does it also have objective normative criteria? The practical difference here is rather consequent. It's also likely the proper intention here also alters the experience itself. Ancient philosophy comprehended the fecundity of heeding the proper end specified by nature, not the end sub specie experientiae, an end that transcended first-person experience. This philosophy said the meaning of all actions is taken from the end, and ends are often not immediately present in the experiencing of the act. Yet, it is the natural end of things and actions that phenomenology struggles to clarify, and thereby is at best impractical, if not misleading, as regards ethical life.

Beyond imaginative cases, I have a real life anecdote on this topic. When I was staying at the homeless shelter of the Sisters of Charity in Rome for a month. A priest from the same order came each Tuesday to give a catechism to the 40 or so men sleeping there in the evening. A good half of them stayed for the talk, and he was going through the ten commandments. My first week there the talk was the 6th commandment, and he hoped to make the catholic take on sexual morality intelligible to these bawdy men, a group of men who were largely not catholic and also not interested in living chastely. The priest, realizing the uphill battle before him, thought the best way to make the teaching of the church intelligible was through his focus on the phenomenological, subjective aspects of John Paul II´s Theology of the Body, rather than the more objective criteria of the thomistic natural law point of view which was also affirmed in the same book. He basically tried to defend the church teaching on the basis of a subjective disposition towards sexual commerce, by saying it's bad to use people for your own wants and pleasure and that true sexual love is about offering yourself as a gift. He tried to ground the teaching on this experiential basis, and he failed. The men wanted to ask about various acts and situations and why that would or would not be appropriate and he struggled to give an account that intuitively made sense. The men, at least, weren't really buying it. If it's about not using people, why is homosexual sex a sin? why premarital sex, or even promiscuous heterosexual sex when both parties are on the same page? Can I not give myself to myself? They already knew what the church taught, and they already knew they disliked the teaching. Now they knew the apparent reasoning behind it and took it to be bogus after his shoddy defense. Iˋm not using anyone, not harming anyone by doing x. Or so they say. And I think they have a point. The easiest way to explain what is missing from x, is to talk about the proper end of sexuality by nature, which the priest failed to do.

In any case, I talked to the priest after and told him the only way to make the teaching intelligible is to talk about the relation between the form and the end, to say that the principal end of the act is procreation. And procreation shouldn't happen, for the children's sake, without the parents being married, and procreation cannot happen with oneself, amongst people of the same sex, or with animals. I said they aren´t going to agree with you that the act is about procreation, I told him, but they will be able to understand. At least in this case you can explain and defend the teaching. And tell them they cannot see eye to eye with it because they are perverts. Anyway, he did, to his credit, actually do this, all except for the last part, the next week he came.

I say this because you cannot get to the form through the proper experiencing of the form with sexual ethics, you just cannot. Attempts to do so are self-defeating. The objective form itself has to be understood as normative in relation to its end. I don't intend to criticize even the phenomenological work in Theology of the Body because it doesn´t seek to supplant but to compliment the thomistic natural law point of view. Yet, the way it was presented in this case by this well meaning priest—and I don't think he is an outlier in thinking this sort of explanation will go over better with denizens of the immanent frame—made me sad. Sad because he hadn´t been given the proper tools to defend the catholic teaching, sad because he was led to believe teaching in a straightforward philosophical manner the real reason for the teaching would not go over well, and thus to avoid it.

Thus, like the man who is afraid to fail, or like the feminist seeking equality, so too the phenomenologist chooses a faulty means to his end, should he be engaging in philosophy for the purposes of living well, that he might know and be perfected by the Good. In the end, the mysticism about experience erodes the richness of experiencing itself, which is contingent upon lofty desires for something that transcends experience. In the end, the attempt to make theory more about life, ends up making life all too theoretical. A phenomenologist can be a commentator, he can even be a guru. In fact they show a predilection for this latter role. But they can´t play, they can’t act well. And thereby nor can they impart wisdom. Again the symptom of this spiritual poverty one finds in the degradation of language itself. Or to highlight the problem (nominalizations disease with a copula!) aping their own abstruse language: The presencing of the verb, which is always already a call, a summons to being, an unveiling in the manifestation that is both a vulnerability and not yet an awakening, in the disclosure of the noun, which both totalizes and violates its object all while ushering in the horizon on which and within which it may call-forth is a symptom of impoverished insight, misanthropy, and just plain bad writing.

you can support me with a small tip here: https://buymeacoffee.com/sweller

At the crux of my argument is that phenomenology is trying to get at the form of things through making sense of our first-person experiencing of the things. The following makes the case for why this is an accurate characterization of the leading phenomenologists.

a. Edmund Husserl.

Husserl´s famous quote “Zu den Sachen selbst!” “to the things themselves!” in Logical Investigations doesn´t mean to the things in a normal sense of the word, as objective or detached, but his focus is to hone in on how the thing is given to first-person experience, or consciousness. This quote exemplifies his approach: "Every object is given through an act of consciousness" (Jedes Objekt ist in Akten des Bewusstseins gegeben) (Ideas I, §88) Again this could be non-controversial. Aristotle, for instance, also seeks a more empirical approach to comprehending the form of things, but for him, the essence of a thing is tied to its purpose or function (telos). It is the movement of the thing towards its end that is most important. For Husserl, the essences of things are grasped through "eidetic reduction," a method where one distills what is essential to something, in contrast, from and through its appearance to and in consciousness. It is this shift of focus which presents problems for the moral life, where the knowledge of final causes is of paramount importance.

b. Martin Heidegger

In contrast to Husserl, who tries to abstract from the superfluous elements of human experiencing of a thing to get at a pure experiencing of the thing, Heidegger in contrast wants to approach a fundamental ontology through the basic structures of human experiencing in the world and in everyday life. “The question of being is nothing other than the radicalization of an essential tendency-of-being which belongs to Dasein itself—the pre-ontological understanding of Being.” (§4, Being and Time). Even here, the opaqueness of heideggerian sentences rears its head. But the focus is to approach the study of being through the explication of the basic structures of human existence, like the ones I list later on in the tennis parable. When these basic structures of human existence or of experiencing the world are uncovered, then the question of the meaning of being can be addressed, which is his whole quest. As with Husserl, the first person subjective experiencing of the world is given pride of place over other aspects of reality, like intersubjective, and emperical realities. Yet rather than abstract from everyday experiencing of things by means of a philosophical method or speculative procedure, Heidegger wants to study dasein in its everyday-ness, in how it experiences being-in-the-world.

c. Emmanuel Levinas

A student of Heidegger, Levinas claims reality, or ethical reality, is constituted primarily through our encounter with the other people. And specifically the faces of other people, who Levinas likes to call The Other. This encounter with other peoples faces breaks through our subjective world and commands us ethically. Levinas says “The way in which the other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the other in me, we here name face... The face of the other at each moment destroys and overflows the plastic image it leaves me, the idea existing to my own measure” (Totality and Infinity (1991), 50-51) Its basically a sort of human face mysticism, as Levinas argues that ethical reality is revealed through the face-to-face encounter with other people. But for him as well the first-person experience, particularly in the presence of another person, is fundamentally transformative in ethical formation. This is perhaps the prime example of misplaced concreteness. Experiencing human faces doesn´t give people who aren´t Emmanuel Levinas a ton of normative content. Its the reification of the bizarre ethical experience of one person. In contast, the entire tradition of aristotelian natural law ethics bases normativity on the entirity of the objective expression of the human lifeform and its tendency and the tendeny of various actions of toward specific ends by nature.

I think C.S. Peirce has a good model for the role phenomenology can play in philosophy. I don´t think the presence of, perhaps bad phenomenological method and analysis in Heidegger, need be a translated into a claim against phenomenology per se, any more than Hegelian Metaphysics might prove that metaphysics is per se sinful. My claim is about the proper object of practical reason and desire and that phenomenology can do little to help us know this object, and that an overreach of this method will pervert the proper object of practical reason and desire.

This type of knowledge can be useful in theory. Husserl´s critique of scientism for instance is good and a good humanistic argument defending the irreducable uniqueness and character of human consciousness. Gadamer´s hermeneutics is also a useful theoretical application. As is Charles Taylors phenomenological defense of human selfhood from materialist reductions in the first two chapters of Sources of the Self. My argument isn´t that phenomenology cannot be usefully employed at the level of theory, it can speak ensightfully about how humans experience and what they experience. Each of these three applications stays within these boundaries. It goes hay-wire at the theoretical level when the first person experience itself is seen as a special window into the nature of things. or reality.

“The sun, I presume you will say, not only furnishes to visibles the power of visibility but it also provides for their generation and growth and nurture though it is not itself generation…In like manner, then, you are to say that the objects of knowledge not only receive from the presence of the good their being known, but their very existence and essence is derived to them from it, though the good itself is not essence but still transcends essence in dignity and surpassing power.” Plato, Republic, 6.509b

"As good has the nature of what is desirable, so truth is related to knowledge. Now everything, in as far as it has being, so far is it knowable. Wherefore it is said in De Anima iii that "the soul is in some manner all things," through the senses and the intellect. And therefore, as good is convertible with being, so is the true. But as good adds to being the notion of desirable, so the true adds relation to the intellect." I q.16 a.3

Conant, James. Two Varieties of Skepticism.

“The fallacy of misplaced concreteness consists in treating as the concrete reality what is in fact an abstraction.” Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality, Part I, Chapter 1.

Stein, Edith. Endliches und ewiges Sein: Versuch eines Aufstiegs zum Sinn des Seins.

Its true, St Thomas doesn´t exactly put it like this in II-II q.167 a.1. In his response here, he says, “Now vanity of understanding and darkness of mind are sinful. Therefore curiosity about intellective sciences may be sinful” He refers to a number of instances of which two are relevant here: (1) “when a man is withdrawn by a less profitable study from a study that is an obligation incumbent on him” and (2) “when a man desires to know the truth about creatures, without referring his knowledge to its due end, namely, the knowledge of God.” Because first person experiential knowledge of things, actions, and ends is of derivative practical import, its both drawing one away from more profitable study, and also, because God is our final End, seeking to know the truth about creatures without reference to God.

Obviously this coach is meant to exemplify Martin Heidegger´s phenomenological critique of the metaphysical tradition in the west from Plato on. Heidegger levies his critique under two banners (1) his critique of “onto-theology” which corresponds with the questioning of the meaning of tennis and (2) his critique of the “Metaphysics of Presence“ which corresponds with the questioning of the existence of an ideal form for a serve, backhand, etc. From the practical point of view, these two critiques attack the end and the means respectively. The new coach calls into question the meaning of tennis, and the proper form for executing the basic movements of the game. This dovetails with Heidegger´s two critiques of the western tradition. “Onto-theology” seeks to comprehend Being as confined by metaphysical project of scholastic theology and it´s study of God. So here the concern is the reduction of Being itself to a being (Almighty God! what sort of pagan could call this a reduction!! of course, Heidegger was a pagan) or beings understood as individual entities, leaving the question of the essence or nature of Being itself unaddressed. In the western philosophical tradition, God is often thought of as a prime mover, the first cause of all things, the final cause as well, and Heidegger sees these sorts of definitions as concealing rather than revealing the mystery of Being itself. So he seeks to liberate being from these theological or conceptual constraints and let “Being be,” through his analysis of the every day existence of dasein. So this attacks the intelligibility of the end, the teleos, just as the tennis coach questions whether playing tennis should be about winning or competitive greatness. And his other critique regards the means to the end. Here Heidegger critiques the “Metaphysics of Presence” in the western philosophical tradition which seeks to know things in a superficial manner, in terms of immediate presence, a static notion of substance, which Heidegger says leads to an alienating form of knowledge (projection, anyone?), a superficial way of knowing that is alienated from practical living and being. Being is temporal, not static, its dynamic and relational, not unchanging. Heidegger says this framing alienates people from being. The analogy is that this new tennis coach rejects, like Heidegger, the notion of ideal forms of a serve or backhand which are universal, unchanging, known in terms of the physical presence of a specific ideal form. These forms likewise alienated players from experiencing tennis according to the new coach. Heidegger´s critique can be found in Being and Time: Division I, Chapter 2, Sections 12-14; 17, also Division II, Sections 62-67. The opening Section of Being and Time explain the Western Tradition´s “forgetfulness of Being” as a philosophical problem.

(Das Man=Tennis Conformity) A tennis player, like anyone else, is often influenced by a public—the collective expectations of how a tennis match should be played according to norms, rules, and traditions. Inauthentic play arises when a player merely follows these conventions without fully activating their personal style or manner of playing the game.

(Eigentlichkeit=Authentic-Play) Authentic play entails engaging fully in the game, demonstrating one's unique skills, tactics, and intentions rather than merely conforming to external expectations or going through the motions of play.

(Auslegung=Tactical-Interpretation) This is how a player interprets the flow of the match, the opponent’s style, and the environment (e.g., the court, weather). The player interprets these factors to form strategies and make sense of their position in the game.

(Befindlichkeit=Court-State-of-Mind) The player’s mood or mental state during the match. Are they anxious, excited, or calm? This existential disposition significantly affects how they engage with the game.

(Verfallen=Falling-in-the-Game) Players have the tendency to lose themselves when facing distractions or disappointments in the game, either becoming too absorbed in trivial matters (like focusing on a single mistake) or influenced by external factors (like the crowd, weather, or referee). In cases like these, a player "falls" into the non-essential aspects of the game.

(Gerede=Idle-Talk)

Tennis play is often threatened by idle talk: the chatter of commentators, spectators, or even the player’s inner conversation at times. This talk often distorts the reality of the game, creating an atmosphere where the player loses focus on the authentic present moment of play.(Entschlossenheit=Match-Resoluteness) The player’s capacity to make decisive, committed moves in the game is crucial. Mentally, he must be free from doubt or hesitation. Resoluteness in tennis entails acting with conviction, taking control of the game with deliberate actions, not retreating from situations where the right movement or move could be subject to doubt.

(Entwurf=Game-Projection) Each movement on the court is always already decided by the players ability to foresee the possible future outcomes in the game (e.g., how points might unfold based on the opponent’s weaknesses). The projection of these onto the future allows the player to strategize and adjust their play accordingly.

(Ruf des Gewissens=Call-to-Fair-Play) The call of conscience discloses itself as a sense of fairness, always already calling the player back to the spirit of the game, to play honorably according to its rules and in the true spirit of competition, not allowing the desire to win to triumph over playing the game in an honorable manner.

I spoke with a Heidegger junkie who hangs out in the Freiburg Uni Bibliothek about this and he suggested the true meaning of tennis revealed as the human desire-to-be-loved, that we play tennis seeking the highest end of love, and every stroke, every serve involves this deep yearning to be loved. This answer pleased me a great deal.

Heidegger wants to consider dasein, human existence, in and through its everyday-ness or its everyday being in the world. And this consideration does generate an ethics of a sort, an ethics of authenticity, this being the subjective quality that determines a good or bad play for Heidegger. An authentic being accepts his mortality, for instance, has a sense of individuality apart from the pressure to conform to the masses. What makes one authentic tend to be subjective qualities like these that struggle to provide objective normative criteria. So my question and the question of this parable is to ask: is this the right focus for human growth in virtue or goodness? Is this misplaced concreteness? Of course I think it is the wrong focus and an instance of misplaced concreteness, and the parable is meant to make clear as to why.

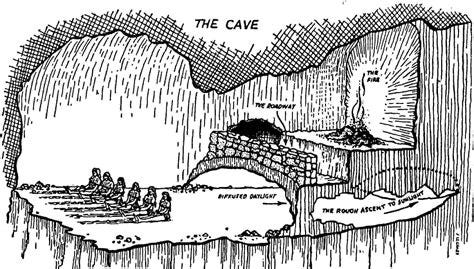

For a further philosophical juxtaposition, consider Plato´s cave allegory: the philosopher´s intellectual recollection of the form of the Good gives light to and quickens human existence towards itself. And it is the knowledge of the cause of the shadows on the cave that turns the philosopher towards the sun. Here, the movement is from a consideration of sensible human form (shadow), to the transcendent cause of the appearance of human form (i.e. the sun), which is, objective, universal, timeless, and distinct from the appearance of the human form on the walls of the cave. Seeking the knowledge of true causes leads the philosophy to recollect the Form of the Good, which both enlightens the philospher and quickens him in virtue towards the ideal form itself. In contrast, the slaves who remain in the cave are enamoured with the sensible shadows they mistakenly think they themselves cause by their own movements, much like the tennis players seeking the proper form from within their own experiencing of the game. Plato would teach tennis the old way and could classify Heidegger´s method as a type of slave-psychology that kept the denizens of cave, by confining them to the limits of their sense experience, from recollecting the proper intellectual form and thereby advancing in virtue.

Read this one expecting to be mad, and you’ve made some brilliant points. The application of curiositas to the fruitlessness of phenomenonology was interesting.

Would be interesting to compare with Metaphysics: “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight.” Also that experience is TW gives the craftsman knowledge of the causes of a thing. So for Aristotle, our “structures of consciousness” being things that reveal our desire to know the Good, and one step on the way to doing so. Anyways—those are just my thoughts that come up in reading.

Have you read Jacques Maritain? His Existance and the Existent is a great (Thomistic) look at experience and ultimate Being.

Former-pastor's kid here: this was fascinating, and brought about a sense conviction that I am currently not educated enough to put into words. The tennis parable was illuminating. Thank you for your thoughts